Polish name: Zaraza ziemniaka

English name: Potato late blight

Kod EPPO: PHYTIN

Gallery

Potato late blight. Symptoms on stems, infection from infected tuber or oospore.

(Photo by J. Osowski)

Potato late blight. Characteristic appearance of necrosis.

(Photo by S. Wróbel)

Potato late blight. White fungal growth on the upper side of the leaf.

(Photo by J. Osowski)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Całkowicie zniszczone rośliny (fot. J. Osowski)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Charakterystyczny wygląd nekrozy (fot. J. Osowski)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Infekcja wtórna przez sprawców suchej zgnilizny (fot. J. Osowski)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Infekcje wtórne przez sprawców mokrej i suchej zgnilizny (fot. J. Osowski)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Objaw charakterystyczny przełamywanie się silnie porażonej łodygi (fot. J. Osowski)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Objawy choroby na ogonkach liściowych (fot. J. Osowski)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Objawy na bulwach – wygląd zewnętrzny (fot. J. Osowski)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Objawy na bulwach – wygląd zewnętrzny (fot. S. Wróbel)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Objawy na bulwach – wygląd zewnętrzny (fot. S. Wróbel)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Objawy na wierzchołku rośliny (fot J. Osowski)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Objawy zarazy na różnych częściach łodygi (fot. J. Osowski)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Objawy zarazy na różnych częściach łodygi (fot. S. Wróbel)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Objawy zarazy na różnych częściach łodygi (fot. S. Wróbel)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Objawy zarodnikowania na kwiatostanie (fot. J. Osowski)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Początek rozwoju infekcji na liściu (fot. J. Osowski)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Rdzawe lub brunatne nacieki nieregularnie sięgające w głąb bulwy (fot. J. Osowski)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Rdzawe lub brunatne nacieki nieregularnie sięgające w głąb bulwy (fot. S. Wróbel)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Rdzawe lub brunatne nacieki nieregularnie sięgające w głąb bulwy (fot. S. Wróbel)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Rozwój infekcji na łodydze (fot. J. Osowski)

- Zaraza ziemniaka. Zniszczony cały obwód łodygi (fot. J. Osowski)

Characteristics and description of the disease

Among the many phytophagous pests attacking potato crops in almost all regions of the world, the dominant culprit is the pathogen of late blight, the fungus-like organism Phytophthora infestans. Crop losses in unprotected plantations can reach 70%. In Poland, losses range from 22-56% depending on the year. In some years, the disease appears on plantations very early, even in May. If the meteorological conditions accompanying primary infections are favorable for the disease’s development, early epidemics of late blight occur throughout the field, leading to premature destruction of the foliage, significantly affecting the yield. In the case of such early infections, potato losses can reach up to 100%.

In Poland, late blight most commonly appears in the second half of June or early July. In recent years, late occurrences of the disease have also been observed – at the end of August or even in early September. However, even in such cases, a rapid development of the disease was visible in many fields, caused by heavy rainfall, leading to the complete destruction of plants. Long-term observations conducted at the Institute of Plant Breeding and Acclimatization-Research Institute in Bonin have shown that even in years when late blight appeared very late in the field, significant tuber infections were noted, often due to the abandonment of early chemical treatments.

The occurrence and intensity of late blight in the field, and later on the tubers, are closely dependent on both meteorological conditions and the source of the pathogen in the field. Prolonged periods of high air humidity, caused by prolonged rains or persistent morning mists or dew (RH>90%), and generally low temperatures (around 15°C) favor the development of the late blight pathogen. If such humid weather persists for several days in June or early July, mass plant infections can be expected. In such conditions, the pathogen’s spores transform into zoosporangia, containing 6-16 motile spores, which are easily released into the environment, causing mass infections.

Lower humidity and temperatures above 18°C cause the spores of P. infestans to germinate directly and infect neighboring plants. The further development of late blight is most intensive at temperatures above 20°C but also with increased ambient humidity. In such conditions, a potato plantation can be destroyed by late blight in just a week, and in extreme cases, even within a few days. The pathogen’s spores have the ability to spread with the wind or rain over distances of several tens of kilometers.

The main sources of plant infection in the field are decaying tubers discarded from heaps in spring, tubers left after spring sorting on waste piles, and unprotected or inadequately protected crops of early varieties in the vicinity. Additionally, the occurrence of P. infestans infection on young potato plants (before plant closure in rows) suggests the likely presence and increasing importance of additional sources of plantation infection originating from the soil. These could include, for example, latently infected seed potatoes. Earlier occurrence of epidemics may also be associated with plant infections by oospores – pathogen’s survival spores (resulting from sexual reproduction), a phenomenon quite common in Scandinavian countries. Oospores can survive in plant residues or directly in the soil, even at low temperatures, remaining viable for a longer time (7-12 months) and serving as another source of primary infection, increasing the pathogen’s infectivity potential in the environment.

On many plantations, the importance of other sources of the disease is also increasing. Volunteer potatoes, grown from tubers left in the field in autumn (warmer winters allow them to survive), are not only an additional source of primary infections in potato plantations the following year. During the growing season, these unprotected plants, grown in subsequent crops, act as “catchers” for the pathogen’s spores in the environment.

The harmfulness of late blight is associated with both a decrease in the yield obtained and the direct infection of tubers. Yield reduction results from the destruction of the above-ground part (assimilating surface) of the potato by the disease, leading to the inhibition of tuber growth. Farmers are well aware that to prevent such a situation and obtain a healthy yield, potatoes must be protected. Late blight-infected tubers decay during storage. They are also secondarily attacked by other fungi and bacteria, further increasing losses.

Symptoms of infection

Symptoms of the disease can be observed on leaves, stems, and tubers. The first irregular, light-green spots are mostly found on the lower, lowest leaves, where humidity is higher. During damp and cool weather, the spots enlarge and turn brown. Early in the morning, with lingering humidity in the air, a delicate white fungal growth is visible on the edges of the spots on the lower side of the leaf, never on the spot itself. On the upper side of the leaf, in the same place, a light-green (celadon) border may appear. With very strong epidemics, sporulation can be observed around the necrosis on the upper side of the leaf (rarely). Developing spots on the leaves lead to the destruction of entire leaves and further, through leaf stalks, to the stems, eventually killing the entire plants. At this stage of the disease, a potato plantation is essentially beyond salvation.

Symptoms of late blight on stems first appear at the tips of shoots, leaf stalks, or various parts of the stems. These symptoms are initially oily brown spots and later turn dark brown. Spots can spread along the stem, encompassing its entire circumference. In this case, leaf infection is a secondary effect, a continuation of the disease process initiated on the stems. Severely affected stems often break at the site of disease occurrence. Field observations have shown that high air temperatures (around 30oC) do not stop the development of the disease but only temporarily slow it down. When conditions favorable for the disease occur, late blight develops epidemically again. Previous observations conducted at the Institute of Plant Breeding and Acclimatization-Research Institute in Bonin indicate several dangers posed by this form of the disease: stem blight can appear on potato plantations much earlier than the leaf form, on some varieties, it develops very rapidly, regardless of weather conditions (even in dry, warm weather), causing mass tuber rotting during harvest. The number of plantations with primary stem infections can vary greatly, depending on the year. The results of observations conducted in the years 2002-2014 on over 400 potato fields show that this form of the disease occurred on average on 50.8% of monitored fields.

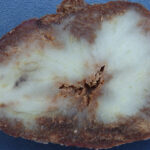

The consequence of late blight occurrence on potato plants is tuber infection. They become infected due to overgrowth of the pathogen, which was present on the stem or leaves. The presence of the disease on tubers can be observed during harvest or storage because late blight-infected tubers rot. Various-sized lead-gray spots form on the surface of the infected tuber. Over time, a pronounced discoloration is observed. Upon cutting a tuber with such symptoms, a rust-colored or brown discoloration extending deep into the flesh is observed. The tissue in these parts of the tuber is quite hard. Such tubers are often secondarily infected by other pathogens, primarily bacteria. They rot very quickly, changing the tissue into a wet or mushy mass.

Methods of protection

The methods of protecting potatoes from late blight involve both chemical and cultural practices.

Chemical protection is based on the application of fungicides, the choice of which depends on the plant’s developmental stage, meteorological conditions, and the expected intensity of disease development. The treatments are typically started after plant emergence (beyond the cotyledon stage) and are repeated every 7-14 days, depending on the susceptibility of the varieties and the rate of late blight development in a given season. Spraying is performed using specialized sprayers that provide proper leaf coverage. The effectiveness of protection is closely related to the appropriate dosage and timing of the application, taking into account the severity of the infection and weather conditions (temperature, humidity, and rainfall).

Cultural practices include the selection of less susceptible varieties, the use of certified seed potatoes, appropriate crop rotation, and the elimination of potential sources of primary infection. Early harvesting and the quick removal of plant residues from the field contribute to reducing the risk of tuber infection. Additionally, planting crops in well-ventilated areas and providing adequate plant spacing to promote air circulation can help reduce the risk of late blight.

Biological control methods are also being explored as a more sustainable alternative. This involves the use of natural enemies, antagonistic microorganisms, or plant extracts to control the late blight pathogen. Research is ongoing to develop effective and environmentally friendly biological control strategies.

In conclusion, late blight poses a significant threat to potato crops worldwide, leading to substantial economic losses if not effectively managed. A combination of chemical, cultural, and potentially biological control methods is essential to mitigate the impact of this devastating disease on potato production.